Following the Civil Rights Trail With Road Scholar

Having practiced civil and women’s rights law for over 10 years, I developed a profound appreciation of what it takes to design strategies, create laws and change institutions to bring about justice and a modicum of equal rights. Visiting the Civil Rights Trail gave me hope that despite what may be coming around the corner for the civil rights of African Americans we will find a way to keep and if necessary, resurrect those rights thanks to the carefully charted course of the Civil Rights Trail.

The U.S. Civil Rights Trail is a massive network of museums, landmarks and churches that cuts across nine states. In fall of 2024, I had an opportunity to join the eight-day Road Scholar Civil Rights Trail program that made over 20 stops along the Trail starting in Atlanta, Georgia and ending in Birmingham, Alabama.

Shortly after embarking on the Trail, I was struck by how little I actually knew about the Civil Rights Movement despite being well versed in African American and African history. In my mind, the Movement was a big amorphous series of events that occurred primarily in the 1950’s and 1960’s that resulted in laws being passed to protect the civil rights of African Americans. Of course, I had textbook knowledge of Rosa Parks, the Montgomery bus boycott, the Freedom Riders, March on Washington and church bombings as well as the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Bayard Rustin, SCLC, CORE, SNCC, etc., but did not really understand the timeline or how all the myriad aspects of the Civil Rights Movement fit together. As I traveled the Trail, the pieces of this fascinating and illuminating puzzle began to fall in place.

The Group Leaders made arrangements for us to have the honor and privilege to meet and talk with people who actually participated in the Movement. The exceptional firsthand accounts from these elders were riveting and educational. One of the highlights was hearing a spell-binding lecture by Attorney Bill Baxley. He prosecuted two of the four Klansmen responsible for the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Avenue church that killed four young girls. He shared the details of how he unraveled the mystery of the identities of the assailants as well as the ingenious legal strategies he used to bring them to justice. I was on the edge of my seat during his entire presentation.

Learning at the Equal Justice Initiative

Of the many places we visited, Montgomery’s Equal Justice Initiative’s three offerings had the most profound impact on me. They were magnificent wonders to behold — the work of geniuses.

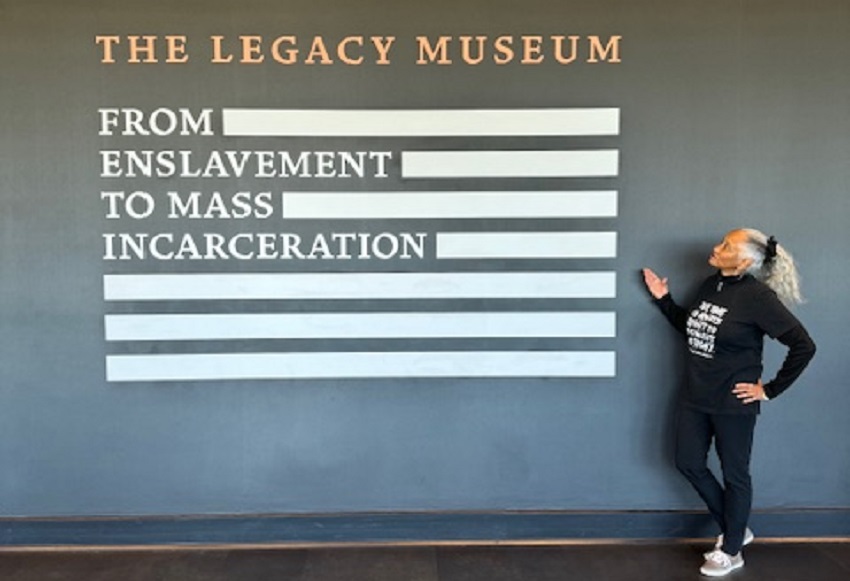

Legacy Museum

From enslavement to mass incarceration, the 11,000-square-foot state-of-the-art museum was designed to strategically engage the imagination of its visitors as the exhibits take them from Africa through the transatlantic slave trade, slave auctions, slavery, post-slavery racial terrorism and the dehumanizing Jim Crow era to present day mass incarceration.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice

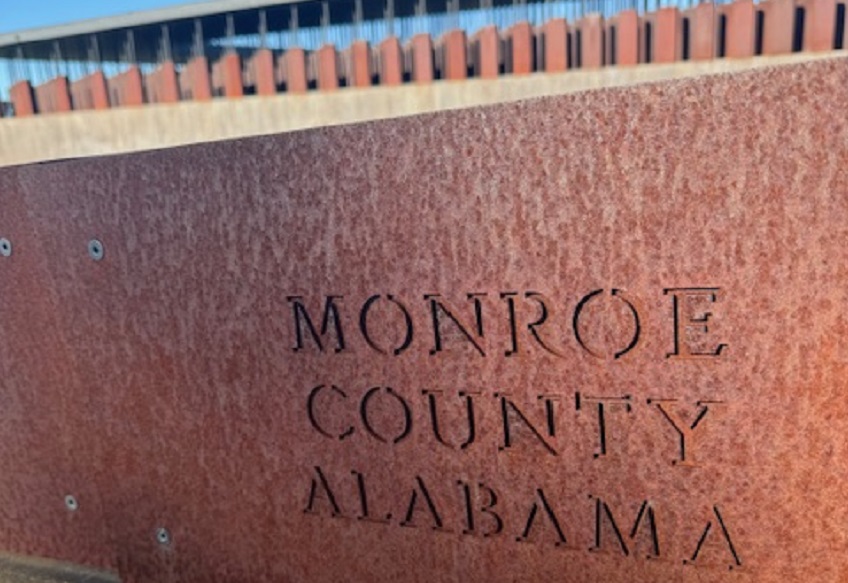

Set on a six-acre site, this is the nation‘s first comprehensive memorial dedicated to the victims of racial terror. The memorial uses sculpture, art and design to contextualize racial terror and its legacy. More than 4,400 Black people were killed in racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950, and their names are engraved on more than 800 steel monuments — one for each county where a racial terror lynching took place.

What made this exhibit particularly challenging for me was visiting the special section that was set aside for the counties of the state of Alabama. My family hails from Monroe County, Alabama so I decided to examine the names listed. Lo and behold, I saw that two of the many names listed carried my family name. I called my older brother to find out if they might be related to us and he told me that our grandfather, Horace Parker (1882-1964), told him that his uncle had been killed by the Klan. I subsequently learned that Monroe County had the third largest number of lynchings of all the Alabama counties. That helped to explain the story my mom told me of how her father, Horace Parker, fled their Monroeville home one fretful night in 1917 for fear of racial terror. She was only 5 years old at the time. A year or so later he sent for the family to join him in the home he had established for them in Albion, Michigan.

Freedom Monument Sculpture Garden Park

This 17-acre site’s sculptures bring a journey through history to life. Art and artifacts provide a unique view into the lives of enslaved people. The park includes works by world-class artists like Kehinde Wiley, Simone Leigh and Alison Saar. The park’s location along the Alabama River, where tens of thousands of enslaved people were trafficked, honors their lives and memories and those of the 10 million Black people who were enslaved in America and celebrates their courage and resilience.

After Montgomery, we went to Selma where we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and visited the Selma Voting Rights Memorial Park. The trip concluded in Birmingham where we visited Kelley Ingram Park, 16th Avenue Baptist Church and the Civil Rights Institute.

Monroeville, Alabama

My ancillary post-Civil Rights Trails side trip included a stop in Monroeville, my ancestral homeland. Thanks to the hard work of researchers that I met with at the Department of Archives & History in Montgomery, we were able to unearth information about my family history including the location of the land where my great-grandfather was born into slavery in 1863 as well as information about his slave owner and his plantation/farm. The researchers also created a map for me to facilitate my ability to find it. They also found my great-grandfather’s death certificate, his 1926 probate proceeding and much more. The visit gave me and my family answers to long-standing legacy questions as well as supplemented the work my niece had previously conducted on Ancestry.com.

My other visit there was in 1961 when my mother and I traveled there during the Jim Crow Era. I still remember how startling it was to learn about and experience America’s apartheid system firsthand.

Mobile, Alabama

I finished my trip with a visit to Africatown in Mobile, Alabama. Even though Mobile is not technically part of the Civil Rights Trail, I found their African American Heritage Trail and Africatown Heritage Center to be fascinating and informative. As you may know, Africatown is an historic community formed in approximately 1865 by a group of 32 West Africans, who, in 1860, were among the last known illegal shipment of slaves to arrive in the United States. On May 22, 2019, the Alabama Historical Commission and partners announced that ship that brought them over, The Clotilda, had been located underwater on the banks of the Mobile River. The Heritage Center chronicles their journey from Africa to Africatown.

The Africatown Hall and Food Bank is the new home of the Africatown Redevelopment Corporation which is executing a plan to revitalize the neighborhood starting with renovating homes in Africatown.

In Conclusion

The entire trip was a magnificent experience that I will cherish for the rest of my life. I am so grateful and gleeful that Road Scholar has taken the time to create and provide such an important, informative and life-changing journey.

Elaine Lee is an attorney practicing in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is also a freelance travel journalist and editor of “Go Girl: The Black Women’s Book of Travel and Adventure” as well as its sequel “Go Girl 2.” To learn more about her work, visit https://www.ugogurl.com/ and/or elaineleeattorney.com.